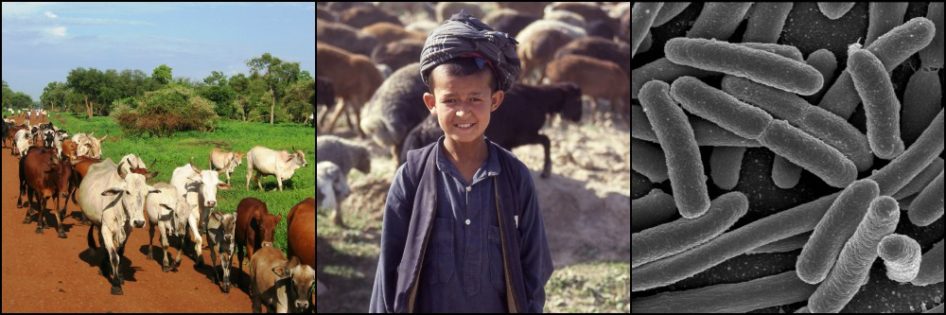

Livestock interventions can offer an effective means of improving livelihoods, food security and women’s and youth empowerment in low-income countries. However, mistaken comparisons to the negative impacts of intensive livestock production in wealthier countries have reduced the popularity of livestock activities among some aid organizations and donors. When projects do address livestock, it is sometimes only an afterthought — a small part of a larger project, planned using a template of popular go-to activities which are not always appropriate for the situation.

This article describes a few of the more common misconceptions surrounding livestock in development and humanitarian work and encourages planners and implementers to take them into account when considering their own interventions.

Continue reading