Ixodes tick, primary vectors for Lyme disease. Jerzy Gorecki

Lyme disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, a bacterium transmitted by ticks to a wide range of animal species (including people) in much of the world. The great majority of human Lyme disease cases in the United States occur in the Northeast and upper Midwest states. Yet, the impact of Lyme disease in the southern US remains minimal despite the abundant presence of the primary Ixodes tick vectors, numerous competent animal hosts, widespread suburban sprawl that brings people into frequent contact with ticks, and the documented presence of B. burgdorferi bacteria in the region. Why hasn’t the disease taken a stronger hold there?

Mixed Emotions

A couple of years ago, I suggested to a client in Florida that it was unnecessary to vaccinate his dog against Lyme disease to protect it on an upcoming trip to Kentucky, which lies outside the “Lyme country” of the Northeast and upper Midwest. After the appointment, my normally coy vet technician pulled me aside.

“I used to live in Kentucky and I know several people there who have Lyme disease,” she said disgustedly, suggesting that I should have vaccinated the man’s dog.

That was my first experience with the deep emotions that Lyme disease so frequently generates (such as the visceral debate about whether Lyme disease can cause symptoms in patients even long after treatment with antibiotics – a subject left for a future post). I had little detailed information on the geographical extent of Lyme disease with which to defend myself at the time. But I decided it would be best to find out more.

Between 20,000 and 30,000 human cases of Lyme disease are reported each year in the US alone, making it the most commonly reported vector-borne illness there. And for every known case, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates at least 9 cases go unreported.

Early symptoms in people include the classic tick-bite skin rash in ¾ of patients, followed commonly by fever, swollen lymph nodes, muscle and joint pain. In untreated cases, the bacteria can spread to cause multiple rashes, facial paralysis, meningitis, and carditis (heart inflammation).

The rash (erythema migrans) that affects 70-80% of human patients with Lyme disease. Similar looking rashes may also be present with certain other diseases or disorders. CDC

Over 95% of US cases occur in the states from Virginia to Maine in the Northeast and primarily in Minnesota and Wisconsin in the Midwest (see map below). Of the remaining 5% of cases diagnosed in other regions, a significant portion are likely acquired during travel to a high-risk state.

In my own state of Florida, for example, an average of 67 human Lyme disease cases per year were reported in the decade from 2002-2011. Over ¾ of these patients reported recent travel to a high-risk region, leaving about 15 locally acquired cases of the disease annually.

With a huge seasonal migration of people from high-risk states each year, Florida has more Lyme disease cases than other southern states, none of which routinely report more than about two dozen cases (including both locally acquired and travel-related cases). This gives an annual incidence rate of between 2 – 4 cases per million people in the south as a whole.

While this compares favorably to incidence rates in the Northeast of well over 500 cases per million people, Lyme disease should not be dismissed in the South. Don’t forget that around 90% of Lyme disease probably goes unreported. And this number may be even higher in the South, as will be discussed below.

These CDC maps demonstrate clearly the overwhelming preponderance of Lyme disease cases in the northeastern and upper Midwest states of the US. The number of cases has increased in recent years much more in these two areas than elsewhere. While Lyme disease is undoubtedly present in the South, it does not appear to be expanding with any urgency, at least in people. CDC

Ticks and the Subtleties of Disease Ecology

We know that Lyme disease vectors, hosts, and pathogen are present in the southern US just as they are in the Northeast and upper Midwest. But something is different in the southern states; something that has so far limited the impact of Lyme disease on the human population there.

Map showing the presence of Ixodes scapularis tick in the southeastern states as well as the northeast and upper Midwest, where Lyme disease is most prevalent. I. pacificus is the primary vector for Lyme disease on the west coast. Amblyomma americanum, implicated in transmission of Southern tick-associated rash syndrome (STARI), largely overlaps with I. scapularis in the southeast. CDC

Part of the answer may lie in tick behavior. At least 8 different tick species in the US have been found to harbor Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria.

Life cycle of the black-legged tick (Ixodes scapularis). Larvae hatch and feed on host; drop off to become nymphs; feed on a different host and drop off to become adult ticks; feed on a 3rd host and the females lay eggs. Larvae acquire B. burgdorferi from infected hosts, then can spread the bacteria to other hosts as nymphs and adults. In eastern states, only the blacklegged tick efficiently and commonly transmits B. burgdorferi between people and other animals. Because of this, it is called a “bridging” vector, unlike the other species that predominantly bite wildlife (and occasionally pets). They are called “maintenance” vectors. CDC

In the northeastern US, the nymphal stages of blacklegged ticks are the primary transmitters of Lyme disease to people. The newly emerged nymphs climb to the top of a blade of grass or bush, waving their front legs to-and-fro to latch on to any suitable animal host that passes by. This is called questing.

Some hypothesize that in the southern states, the heat and strong sunlight discourage questing because the ticks, particularly in the immature stages, can easily dry out if a meal is not quickly found. The ticks instead prefer to hang out under the leaf litter, where they feed on lizards and small rodents rather than the larger mammals and birds found by questing ticks.

Lizards in particular are thought to be poor vectors of B. burgdorferi and often fail to pass on their bacteria to feeding ticks, thereby limiting the burden of disease in the environment.

Western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis) with an embedded tick on its shoulder. This lizard species has been found to make a blood protein that causes B. burgdorferi bacteria to die once in the midgut of a tick nymph that is feeding on the lizard. Similar qualities could potentially exist in reptilian hosts in southern states as well. Jerry Kirkhart

Ixodes scapularis female adult on left, nymph on right. The latter are much more likely to go undetected on a person before taking a blood meal. Griffin Dill

Such behavioral differences may also help explain the fact that people are more likely to be bitten by a blacklegged tick nymph in the northeastern US (where questing is less of a danger to them), and more likely to be bitten by an adult in the South. As adult ticks are much larger than the nymphs, they are more likely to be found crawling on a person’s leg or arm and discarded before it has time to take a full blood meal. This greatly reduces the risk of Lyme disease and, again, may contribute to the lower incidence of the disease in the South.

Various stages of the Ixodes ricinus tick, the primary vector of Lyme disease in Europe. These demonstrate the significant size differences in the various stages and why it is more likely that the immature tick stages will go undetected by their prey when seeking a blood meal. Left to right: unfed larva; engorged larva (following blood meal); unfed nymph; engorged nymph; unfed male adult; unfed female adult; partially engorged female adult. Alan R Walker

Diagnostic Dilemmas

Lyme disease is not on most people’s radar in the South, including many physicians, and there are undoubtedly numerous undiagnosed or misdiagnosed cases there. In high risk areas, a patient with the classic skin rash and a history of exposure to ticks is often treated for Lyme disease without any testing, so likely is the diagnosis.

However, when the rash and history of tick exposure are not present, or in areas where Lyme disease is uncommon, the recommended diagnostic protocol involves an initial test to identify antibodies against B. burgdorferi in the patient’s blood (either an enzyme immunoassay or an immunofluorescence assay). A positive or uncertain result should be followed by a second, different antibody test (immunoblot) to confirm.

If the patient was infected several weeks earlier, the victim’s immune system has had ample time to produce antibodies against the bacteria. The 2-tiered diagnostic testing protocol accurately detects over 70% of these infections. In the first weeks of infection however, antibodies are rare and the testing protocol successfully diagnoses only 30-40% of these cases.

So testing for Lyme disease early on has severe limitations, another reason that physicians in high-risk areas will treat suspected early cases without testing.

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria. Notice the cork-screw shape of these spirochete bacteria. CDC

The specificity of the Lyme disease testing protocol is fortunately much better (over 95%). This means that “typically” when you get a positive test result for antibodies to B. burgdorferi, you can be pretty sure that these are indeed antibodies to B. burgdorferi, and not a cross-reaction with antibodies to similar bacteria.

I say “typically” above because this holds true when the disease you are testing for has a pretty good likelihood of being present. When you get a positive test result on a patient in the Northeast with a fever, rash, joint pain, and history of tick exposure, the physician can feel good about treating that person for Lyme disease.

Unfortunately, when the disease being tested for is rare, you have to be much more careful with interpreting a positive result, even when the specificity of the test is high. This is called the predictive value positive, i.e. how much faith you put in a positive test result under given circumstances.

Borrelia burgdorferi is one of 20 or so very similar bacterial organisms, several of which are found in ticks, people, and other animals in the southern US. It is speculated that some positive test results for Lyme disease have been due to cross-reactivity of the tests with these other bacteria.

One recent study found a positive predictive value of only 10% for patients in a low-risk area with no history of travel to a high-risk area, even when using the recommended 2-tiered testing. In other words, only 1 in 10 positive test results are accurate for such patients. Such false-positives would exaggerate the true number of cases in the South. But since Lyme disease is rarely suspected and tested for there, its impact has likely been low.

Ixodes ticks, primary vector of Lyme disease in the US. Clockwise from upper left: engorged adult tick laying eggs; tick feeding on a person; adult tick questing on leaf blade; adult tick. Michael Wunderli

The water has been further muddied by STARI, short for southern tick-associated rash illness. This was coined after a number of patients, mainly in the southern US, showed Lyme disease-like symptoms but in whom no causative agent, including Borrelia burgdorferi, could be found. Because of their similar symptoms, STARI has undoubtedly been misdiagnosed as Lyme disease on many occasions, and vice versa.

The Dilution Effect

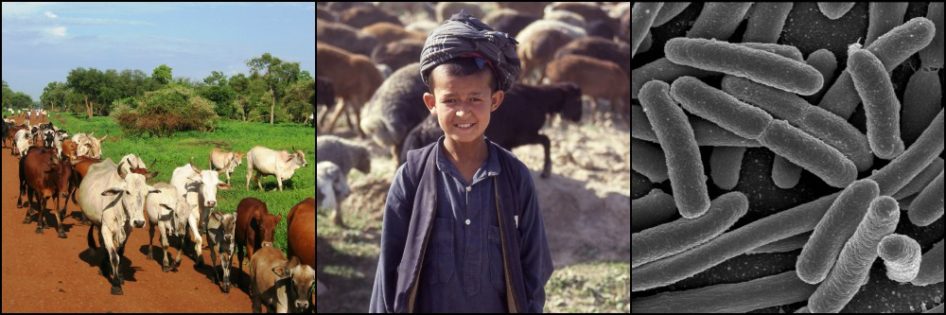

Finally, as was touched on in my previous post on migratory birds as spreaders of emerging diseases, greater diversity of B. burgdorferi host species in the South may dilute the bacteria’s effects compared to the Northeast.

Ixodes ticks in the South have an abundance of mammalian, avian, reptilian, and amphibian hosts on which to feed. Many of these hosts are poor transmitters of the Lyme disease pathogen, so the chances are relatively high that a tick won’t ever be infected by B. burgdorferi.

On the other hand, when only a few host species are available to feed ticks in a given ecosystem, and when many of these hosts are highly competent transmitters of B. burgdorferi, the chances are very high that an individual tick will become infected during one of its meals. This dilution effect may be another factor in Lyme disease’s scarcity in the South.

Maps showing high endemic species richness in the southeastern United States, particularly mammals, reptiles, and amphibians, key players in Borrelia burgdorferi epidemiology. PNAS

Any number of other factors may play a role in Lyme disease epidemiology. Slight differences in the genotypes of both blacklegged tick and Borrelia burgdorferi populations between the northeastern and southern US have been described and could be significant. But there are huge gaps in our knowledge of these and many other subjects not addressed here.

The veterinary technician from Kentucky who scolded me about Lyme disease in the South was right in bringing to my attention that the disease is indeed present there. Yet the very low number of cases makes it unlikely that she knows “several” people diagnosed with the disease, as she claimed.

Research has uncovered much, but why Lyme disease is not more prevalent in the southern US, despite the presence of required vector, hosts, and pathogen, remains a mystery.

References

Clark KL, Leydet B, and Hartman S. Lyme Borreliosis in Human Patients in Florida and Georgia, USA. Int J Med Sci. 2013; 10(7): 915-931.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lyme Disease and Other Tick-Borne Diseases. Critical Needs and Gaps in Understanding Prevention, Amelioration, and Resolution of Lyme and Other Tick-Borne Diseases: The Short-Term and Long-Term Outcomes. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011.

LoGiudice K, Ostfeld RS, Schmidt KA, and Keesing F. The ecology of infectious disease: Effects of host diversity and community composition on Lyme disease risk. PNAS. 2003 Jan; 100(2): 567-571.

Moore A, Nelson C, et al. Current Guidelines, Common Clinical Pitfalls, and Future Directions for Laboratory Diagnosis of Lyme Disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jul; 22(7): 1169-1177.

Although the genetic differences between northern and southern Ixodes scapularis populations are “slight” (in that they don’t reach the level of being two different species) they underpin a behavioral difference between northern and southern nymphs that is an important part of this story: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0127450