Despite great leaps in rabies prevention, the virus still kills over 50,000 people around the world each year. While poorer countries need better access to rabies treatment, wealthier countries arguably have too much access, leading to millions of dollars in unnecessary treatments. This deadly disease is more complex than first meets the eye, favoring specific host species in a given geographical area, and in some cases even allowing its victim to survive the infection. This post and the next explore some of these complexities.

The December 2015 report of a rabid dog imported into the US from Egypt with a falsified rabies vaccination certificate highlights the complexities of this deadly disease and the significant disparities in rabies control efforts around the globe.

Wealthier countries have made huge strides in controlling rabies since the discovery of a vaccine in 1885. Vaccination campaigns have eliminated the circulation of the virus among domestic dogs in the US, Western Europe, and Japan, among others, with reports of rabid dogs in the US declining from nearly 7,000 at the end of WWII to fewer than 100 in 2013.

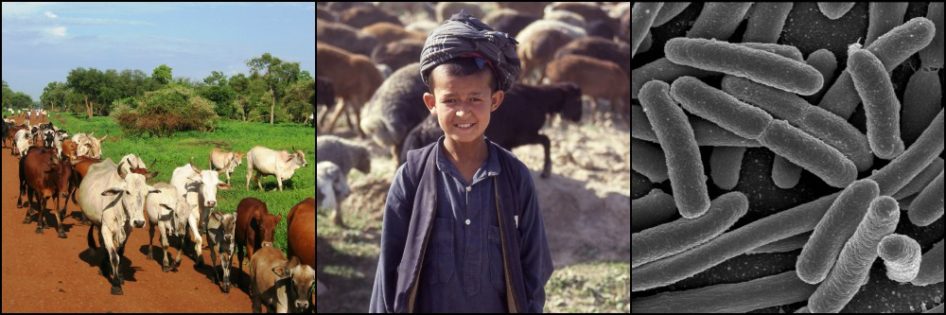

Human cases have followed suit, dropping from over 100 annual deaths in the early 1900s to 3 cases per year in the US today. Despite these successes, rabies continues to kill over 50,000 people each year, the majority in Asia and Africa where rabies is maintained by large populations of stray dogs.

A Gruesome Disease

I long held a simplistic view of rabies as a singularly uninteresting disease: a person or animal is bitten by an infected, furious, drooling animal and the victim is either vaccinated and lives, or is not vaccinated and inevitably suffers a gruesome death a few weeks later. Rabies seemed to possess none of the ambiguities that make some diseases so fascinating.

But rabies is more subtle than I gave it credit for. The disease is caused by a virus that, once injected under the skin, multiplies slowly in the muscle fibers before making its way up surrounding nerves to the brain and then into the salivary glands. Inability to swallow causes virus-laden saliva to accumulate in, and drool from, the mouth, while encephalitis (brain inflammation) provokes aggressive behavior in 80% of victims. This choreographed play, written over generations, is exquisitely designed to facilitate viral transmission to other hosts.

Reports from India, with more human cases than any other country, offer insights into various manifestations of the disease. The behavioral changes prompted by rabies, including sexual aggression in some cases, are commonly misdiagnosed in India (and elsewhere), with patients ending their days in a psychiatric hospital.

More Subtle than First Meets the Eye

Several genetically distinct variants of the rabies virus exist, each with its preferred host animal. While there is some overlap, usually just one terrestrial mammal (as opposed to bat) variant exists in a given geographical area. In the US, where the domestic dog variant has been eliminated, wildlife accounts for 90% of the several thousand rabid animals diagnosed each year. Raccoons, skunks, foxes, and bats each have their own variant, in some cases more than one.

Up to the late 1970s, the raccoon variant rabies was limited to Georgia and Florida. But a decade after the release of suspected rabid raccoons into Virginia at that time, raccoon rabies replaced skunk rabies as the most common terrestrial variant in the US. It is now present across the entire eastern US, from Florida to Canada and west to Ohio.

Non-bat rabies virus variants by region in the US. CDC

Bat rabies variants are the most common and account for a majority of human rabies cases acquired in the US and other developed countries today. This is likely because most sober people notice when they have been bitten by a raccoon, skunk, or fox and are able to seek medical attention. But a bite with the tiny, needle-like teeth of a bat may be overlooked. Nonetheless, the threat from bats is less than previously suspected, with less than 1% of individual bats carrying the virus.

Rabies variants are significant because they do not spread easily outside of their preferred host species. In areas where skunk rabies dominates, for example, the virus is perpetuated through spread from one skunk to another. Occasionally a raccoon, fox, or even an opossum (contrary to popular belief) will become infected from a skunk and die. But these latter animals are essentially dead-end hosts, rarely spreading the virus to others.

One example of this is the cat, the domestic animal most commonly reported to have rabies in the US. Yet, surprisingly, no cat variant of the rabies virus exists. The disease will die out in a cat population in the absence of some other animal species perpetuating its own variant of the virus nearby.

Some animal species aren’t even susceptible to certain rabies variants. Raccoons, for example, are highly resistant to infection by the skunk variant. People, with no variant of their own, are fairly resistant to rabies. Based on records prior to development of a rabies vaccine, an estimated 50% of untreated bites from rabid animals to humans fail to produce the disease. But those odds still aren’t great!

Contrary to my belief when I snubbed rabies as unexciting, the disease is NOT uniformly fatal in its victims. Unvaccinated, healthy raccoons and bats can harbor antibodies to rabies virus, suggesting they were exposed to and survived the virus in the past. Antibodies found in unvaccinated people in the Peruvian Amazon with frequent exposure to vampire bats stirred up much interest a few years ago, though interpretation of the results is under debate.

Nevertheless the disease in people, once symptoms appear, is for all intents and purposes fatal. Treatment by inducing a coma in a young girl after the appearance of rabies symptoms in 2004, and who later recovered, has failed in all but a handful of cases since then. And even those are controversial. Some patients may not have had rabies at all. Others received rabies vaccine prior to coma induction. This so-called Milwaukee Protocol is generally not recommended by public health authorities today.

Dog with classic signs of rabies

With the onset of rabies symptoms, vaccination is no longer of use. It even speeds up the disease process. The key is treating prophylactically, during the incubation period before symptoms appear. This is called post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and comprises the injection of rabies immunoglobulins into the wound site and a series of 4-5 vaccinations.

Awareness is a Double-Edged Sword

For PEP to be sought out, the exposure to rabies must be recognized. A typical example in the US, and one I saw in vet school, is a farmer who has a cow with something “stuck in its throat,” a classic sign of rabies in cattle. The farmer extends his bare arm into the animal’s mouth to try to dislodge the object, but finds nothing. It is up to the veterinarian to suspect rabies in the cow and advise the farmer to seek medical advice.

Rabies awareness has saved many people who knew to seek PEP after an exposure. But awareness can be a double-edged sword. Direct costs alone for PEP exceed $3000 per patient in the US, and overtreatment (of low-risk exposures) is rampant. An estimated 35,000 people received PEP in the US in 2014, primarily for possible bat exposures, costing over $100 million.

My first year out of vet school, I saw an old dog with neurological signs one evening in my clinic. He was an indoor dog, but several years overdue for his rabies vaccine. As the dog’s condition deteriorated, I said to my nurse, “We have a dog long overdue for its vaccines with neurological signs and no obvious cause. We should probably wear gloves, just in case it’s rabies.”

If I had only left out that last phrase.

The dog soon died from widespread internal bleeding – which largely ruled out rabies as a diagnosis. However the 4 or 5 nurses that had handled the dog were understandably concerned and wanted PEP, which they got. The PEP was unnecessary, but I had only myself to blame. A valuable lesson in communication.

In wealthier countries, the problem is too much PEP. In poorer countries, PEP is beyond the reach of the average citizen. Many do not seek treatment, or otherwise do not follow through with the full course, which partly explains why over 50,000 people still die from this easily preventable disease each year.