Ankole breed cattle near Lake Mburo National Park, Uganda. Stephanie L. Smith

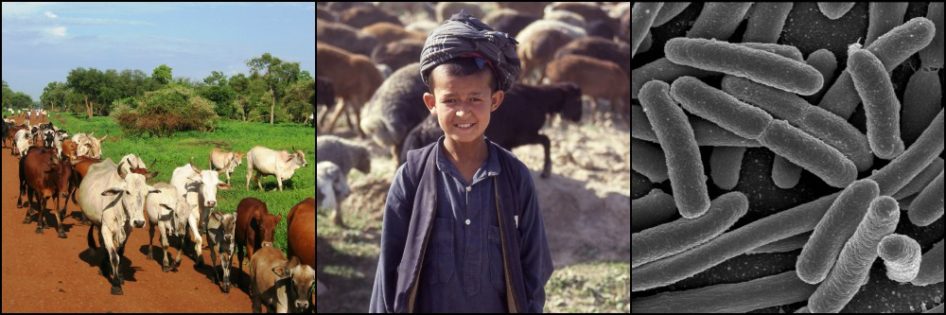

Uganda is one of numerous countries around the world to have signed on to the UN Food & Agriculture Organization’s Progressive Control Pathway, aimed at reducing and eventually eliminating foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) from livestock herds. When I witnessed an FMD outbreak in Uganda 8 years ago, control efforts there were hampered by lack of resources, poor infrastructure, and pastoralists wary of government attempts to intervene and whose social traditions and economic necessities often clashed with disease control measures.

While these barriers have not disappeared today, Uganda has made improvements that place it in a better position to overcome the losses generated by this disease. These obstacles are not unique to Uganda, and the lessons learned here offer valuable assistance to nearly all countries embarking on the pathway to FMD elimination.

Foot-and-mouth disease is caused by an RNA virus and affects only cloven-hoofed animals, including cattle, sheep, goats, swine, and various wildlife. The most striking feature of infected animals are fluid-filled swellings (called vesicles) on the gums, tongue, lips, nostrils, teats and around the hooves. The vesicles rupture and are very uncomfortable, resulting in lameness and drooling because it is too painful to swallow.

While few adult cattle actually die from FMD, over 20% of infected calves may perish. But it is the abortions, often permanent drop in milk production, unthriftiness, and chronic fertility problems in recovered animals that make FMD such an economically costly disease.

Cattle typically become ill 3-5 days after exposure to FMD virus. The disease runs its course over 2-3 weeks, and is spread between susceptible animals through contact with vesicular fluid, saliva, and nasal secretions, or through drinking of contaminated milk by nursing animals.

Top left: Typical foot-and-mouth disease vesicles and erosions in the oral cavity of an infected cow, Lake Mburo, Uganda, 2009. Stephanie L. Smith

Top right: Erosions on the tongue of an animal infected with FMD virus. These painful lesions make it difficult for the animal to swallow, resulting in drooling.

Bottom: Typical erosions around the snout of a pig infected with FMD.

The Outbreak

I spent part of the summer of 2009, while still a veterinary student, in Uganda working with the country’s veterinary Diagnostics & Epidemiology Center in Entebbe. Soon after my arrival, a District Veterinary Officer reported an FMD outbreak around Lake Mburo National Park in southwest Uganda. A focal point of the disease was a livestock watering hole near the park: a 2 meter-deep, 100 m x 50 m reservoir dug out of the red clay soil. Herders used jerry cans, a pump, and PVC pipe to transfer water from the reservoir to 3 tin troughs, from which 5-6 cattle could drink at once.

Over 2500 head of cattle divided into several dozen herds drink from this reservoir every day during the short (December-January) and long (May-August) dry seasons. A single herd is brought up to the troughs while the next waits nearby for them to finish and move off. But the separation of herds is illusory and the cattle frequently mix with one another.

The herders here told us that sores on the gums and around the hooves plagued many of their animals. A veterinarian from the diagnostics center convinced the herders to allow us to take samples from the affected cattle.

Left: Map of Uganda, showing Lake Mburo National Park as a red bull’s-eye and the region inhabited by the Ankole people in green. The Ankole homeland is called Banyankole, sometimes written, as in this map, as Banyankore (the ‘R’ and ‘L’ sounds are often pronounced identicially in this and other Bantu languages). History of Uganda

Right: Map of Lake Mburo National Park, with the site of the 2009 FMD outbreak marked with a dark blue star near the top of the map. ATAdventures

As we swabbed the open sores, collected fluid from deep in the throat, and drew blood from the tail vein of 50 or so animals, the herders became impatient. They complained that our sampling was hurting the cattle.

But they were unhappy for another reason too: the government had vaccinated some of these herds for FMD only 10 days or so before this outbreak erupted.

FMD virus comes in 7 slightly different forms, or serotypes, and each serotype is further divided into one of over 60 subtypes. Vaccines against any one viral subtype provide protection only against that subtype, and sometimes against a handful of closely related subtypes. Uganda, like nearly all areas with regular FMD occurrence, is affected by multiple subtypes and serotypes (A, O, SAT-1, and SAT-2, in the case of Uganda).

The forlorn veterinarian explained to the pastoralists that the vaccine used recently may not have included the virus subtype affecting their animals at that time, adding that time is also required between an animal’s vaccination and its being protected from illness. Ten days may not have been long enough.

The herders were not completely convinced.

Official foot-and-mouth disease status by country. In most of the “countries and zones without an OIE official status”, FMD is present or occurs relatively commonly (i.e. is enzootic). The single red area (“Containment zone within a FMD free zone without vaccination” status) in western Russia is due to a small FMD outbreak in October 2016 in livestock not far from an FMD vaccine manufacturing plant. See Pandora’s Box? The Risks of Pathogen Escape from Laboratories for details. OIE

Priorities

The herders we talked with agreed without exception that they would love to be rid of FMD. But when we discussed ways to fight the disease, the challenges came into focus.

Isolation or quarantine of affected herds would prove next to impossible as these livestock depend on constant movement to find pasture and water. This and many other water reservoirs were already drying up with heavy use from expanding herds. Yet any suggestion of restricting herd size is politically sensitive.

Lake Mburo is surrounded by an arid savanna and forms the heart of the 260 km2 Lake Mburo National Park (LMNP). Since bringing tsetse fly populations under control here in the 1960s, some 50 commercial cattle ranches have mushroomed around the lake. A game reserve was established at the same time, becoming a national park in 1983, part of a concerted effort to attract tourists to the country.

These changes also attracted an influx of Ugandans to the area, with the inevitable clearing of land for agriculture and efforts to secure land ownership. Competition for scarce grazing and water resources between pastoralists on the one hand, and commercial ranches, farmers, and the national park on the other, have caused tensions.

The Problem of FMD Carriers

Anywhere from ¼ to ½ of cattle in FMD regions may be chronic carriers of the virus, for up to 3½ years in extreme cases. Vaccination reduces the chance of an individual becoming a carrier, but does not guarantee it. In theory, such carriers may seed new outbreaks when the conditions are right, though just what these conditions are is not clear.

In sub-Saharan Africa it is not even clear if livestock regularly transmit FMD virus between one another. The majority of livestock cases here are believed to acquire the virus directly from wildlife. Around Lake Mburo, African buffalo, impala, eland, topi, warthog, waterbuck, and possibly hippopotamus are all susceptible to FMD infection. Moreover, herders frequently use the national park lands (illegally) as a source of pasture and water for their livestock, mixing them with potential wildlife FMD carriers.

However, despite the numerous susceptible wildlife species, only the African buffalo is known with confidence to regularly transmit FMD virus to livestock. Infected buffalo calves become ill and for two weeks shed high amounts of virus that can infect livestock. Adult buffalo on the other hand rarely show clinical signs from FMD, but may remain carriers for up to 5 years. Well over half of the individuals in some buffalo herds may be carriers at any given time, spreading the virus to the calves.

African, or Cape Buffalo (Syncerus caffer) are believed to be the major, if not only, transmitter of certain foot-and-mouth disease virus serotypes in Africa (SAT-1, -2, and -3), occasionally spreading the virus to livestock they come into contact with. This photo illustrates well a description I once heard: “Cape buffalo stare at you as if you owe them money.” Charles Hoots

With the recovery of wildlife numbers around Lake Mburo, ranchers and pastoralists alike have come to view wildlife as competitors and reservoirs for disease. Tourism generates hard currency for the country, but pastoralists view anti-poaching regulations in the park as tending to further increase wildlife numbers at their expense.

When FMD Strikes – In Theory

Uganda’s FMD efforts have focused on control measures more than on prevention, and average costs come to half a million dollars US annually. The presence of FMD in all of Uganda’s neighbors, combined with porous borders, has persuaded policy-makers that the disease will likely not be kept out of Uganda without huge costs. The government feels hard pressed to justify the resources necessary to eliminate FMD, given that it kills very few livestock, does not directly affect human health, and does not significantly impact Uganda’s bottom line (livestock-related exports to FMD-free countries would likely not be a significant part of the economy even if FMD were eliminated).

When FMD broke out during my visit in 2009, Ugandan authorities promptly banned the movement of cattle from the affected area until further notice. Checkpoints were established on the main roads, where police verified papers to ensure livestock were not leaving the isolation area. Cross-border livestock movements between Uganda and nearby Tanzania were also halted.

Butcher shops and cattle markets were closed and ruminant livestock and meat were forbidden from leaving the immediate area. Milk could only leave in refrigerated, sealed tanks and go directly to processing plants. Raw milk sales were forbidden even within the affected area.

Finally, FMD vaccines were ordered from KARI Veterinary Vaccines Production Center in Nairobi, Kenya for a vaccination campaign working outwards from the affected areas.

Ankole cattle around Lake Mburo National Park. Their Hima owners value these animals according to horn size and shape and hair color in particular, with milk production only of secondary importance. Stephanie L. Smith

When FMD Strikes – In Practice

This FMD control strategy – of vaccination, isolation, and restricted cross-border movements of livestock, along with reinforced disease surveillance throughout the country – faces many hurdles in Uganda, as it does in all countries.

Outbreaks in isolated rural areas may take weeks for government authorities to hear of and confirm FMD as the culprit. Unscrupulous traders, anticipating isolation of the affected regions, sometimes buy up cattle there at bargain prices and transport them to other areas before road checkpoints are established. That can partly explain how FMD outbreaks have spread rapidly to distant regions of Uganda.

Restrictions on how and when animals can be sold during an outbreak translates into significant hardship for poorer livestock owners. The semi-nomadism of some pastoralists makes quarantine and isolation measures very difficult to implement. Significant manpower is required to separate FMD-exposed herds from unexposed herds. And the animals would still have to be watered from the same scarce water points and graze on the same scarce rangelands.

It takes on average 7½ weeks between the time an FMD outbreak is confirmed and the arrival of vaccines. Some years ago, I visited a Ugandan District Veterinary Office near the Tanzanian border where an FMD outbreak had been found six months earlier. The vaccine arrived the same day I did. Though requiring refrigeration, the vials were stacked in the DVO office for lack of sufficient refrigerator space. An employee was sent off the same day on a bicycle with vaccines in a small Styrofoam cooler and a few chunks of ice. They would quickly be rendered useless in the day’s heat.

Ankole cattle grazing around Lake Mburo, Uganda. Stephanie L. Smith

Options Going Forward

But Uganda’s options on the pathway to better FMD control are numerous. One strategy employed by some countries is a prophylactic vaccination campaign to prevent outbreaks before they occur. This is costly, as an estimated 80% or more of cattle would need to be vaccinated to be effective, and strong immunity to FMD only occurs after several boosters. Any interruptions in the vaccine schedule risks even more severe FMD outbreaks.

As such, a strong political commitment and steady supply of good quality vaccines, along with funds to pay for them, are critical before embarking on such a campaign. As we have seen in a previous post, vaccination without complementary control and prevention measures tends to be ineffective at best.

The combination of porous international borders, the mobility of pastoralist herds and wildlife, the concentration of large numbers of animals at watering holes in the dry seasons, and difficulties enforcing livestock movements all make it difficult for Uganda to eliminate FMD from livestock. But not necessarily impossible.

Gaining the support of the pastoralist population will be critical to successfully address FMD. Yet they are unlikely to offer wholehearted support so long as the question of livestock-wildlife interface is not addressed and/or pastoralists do not share in some of the proceeds from tourism that the wildlife are meant to attract.

Uganda’s goal is to have no more FMD outbreaks by the year 2024. To achieve this, the country has recently completed a new biosafety level 3 laboratory at the lab I visited in 2009, now called the National Animal Disease Diagnostics and Epidemiology Center. This will allow improved diagnostic testing for FMD virus in suspected outbreaks, saving time and allowing for more rapid ordering of vaccines.

In addition, a stronger network of District Veterinary Officers around the country can improve early detection of FMD outbreaks in remote areas of the country, decreasing the costs of control.

These improvements are critical components to a successful FMD prevention program not only in Uganda, but in any country.

References

Alexandersen S, Zhang Z, and Donaldson AI. Aspects of the persistence of foot-and-mouth disease virus in animals—the carrier problem. Microbes and Infection. 2002; 4(10): 1099–1110.

Namatovu A, Tjørnehøj K, et al. Characterization of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Viruses (FMDVs) from Ugandan Cattle Outbreaks during 2012-2013: Evidence for Circulation of Multiple Serotypes. PLoS One. 2015; 10(2): e0114811.

Tekleghiorghis T, Moormann RJM, et al. Foot-and-mouth Disease Transmission in Africa: Implications for Control, a Review. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2016; 63(2): 136-151.

Tukahirwa, Joy. 2002. Policies, people and land use change in Uganda: A case study in Ntungamo, Lake Mburo and Sango Bay sites. Land Use Change Impacts and Dynamics (LUCID) Project Working Paper 17; Nairobi, Kenya: International Livestock Research Institute.

A really clear and readable account of the real life challenges of controlling disease in the field and the importance of understanding community behaviours and motivations as well as the science of disease pathogens.

Such a great read, I come from Uganda and know the cattle keeping areas well as well as keeping a few cows. I have been asking myself questions about the epidemiology and control of FMD and this is the first well written article about it in the Ugandan (maybe African as well) context.

Thanks a lot and will share this widely.

I do really wonder though why no greater effort is made to provide multivalent vaccines on the market, my belief and experience is the pastoralists are willing and able to pay for the vaccines in order to protect their livelihood